A Cambodian history lesson

I didn't know much about its history before our visit, but as soon as you start researching a trip to Cambodia, you realise how important it is to understand the very recent troubles the country has faced.

The Khmer Rouge came into power in Cambodia in 1975, with Pol Pot as their leader. Over the following four years, people were forcibly moved from cities to live in work camps in the countryside and anyone deemed to be educated (even if that just meant wearing glasses) was brutally killed. Starvation, child soldiers and torture were part of everyday life, and by 1979 25% of the population had died.

The effects of this are still so evident today, uncleared land mines regularly kill people in the countryside. Walking around, the population feels very young, you rarely see older people.

To commemorate the victims and educate people about the genocide, there are a number of sites open to visitors in Cambodia. Two of the most well known ones are in Phnom Penh, the Choeung Ek Killing Fields and the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum (also known as S-21).

During Pol Pot's regime, Choeung Ek was an execution camp where 20,000 people were buried in mass graves. The horror of what happened here is hard to comprehend, the 8000 skulls in the memorial building, the clothing and bones that have worked their way to the surface of the graves over time, the tree where children were bludgeoned to death to save on bullets. It's now a memorial where people can leave flowers and friendship bands for the victims.

The Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum was originally a school before the Khmer Rouge turned it into a prison. It's a site where 30,000 Cambodians and also some foreigners were held and tortured for months before being killed.

The prison has been left as it was, with the cells still in tact and the rooms left bare apart from torture instruments on iron bed frames. Everyone walked around this place in silence.

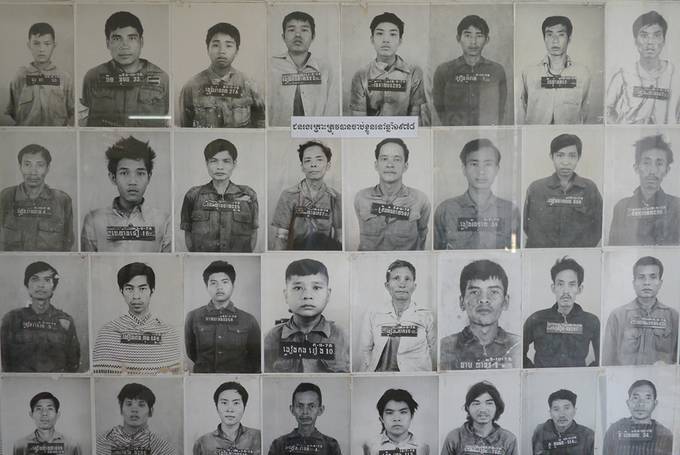

The Khmer Rouge kept meticulous records and everyone who entered the prison had their photograph taken. The sheer number of portraits here, at just one of the 150 similar execution centres around the country, is staggering and what it means for 2 million people to be killed starts to sink in. A number so large that it's hard to comprehend.

In the last room, there's a shrine where you can pay your respects to the victims. While we were there, a family were lighting incense in remembrance of people they'd lost. This all happened so recently and affected so many, every Cambodian will have lost someone.

There are no words to express just how difficult it is to visit these places. They leave you with so much admiration for the way that the Cambodian people have moved on from this tragedy, without counselling or treatment, and remain so warm.

If you want to find out more about Cambodia's history, the memoir First They Killed My Father by Loung Un, is a heart-breaking insight into the experiences of a young girl who lived through the genocide.

—Yasmine